Historical Facts – 10 Unexpected Discoveries from Royal Tomb Excavations

it’s tempting to assume that by now we surely must have found everything on earth that is there to be discovered. After all, people have studied the excavated remnants of the cultures before them for centuries, even though archaeology as a field with specific methods was only professionally established in the 18th century. What could there be left after all these centuries of digging up the treasures of the past?

Surprisingly, there are several tomb sites of historically significant personalities that are yet to be found. We have not found, for example, the tomb of Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongolian Empire, as well as that of Nefertiti, the queen of Egypt that became famous for her bust which was discovered in the workshop of Thutmose.

A reason why there are quite a few important sites that have not yet been excavated is that far too often modern civilizations erected buildings and whole cities on sites where unknown secrets are buried.

Archaeologists have always been fascinated by the tombs of ancient rulers and royals. Since these powerful figures were able to employ excellent artists and craftsmen and had masses of workers and expensive materials at their disposal, they were able to make sure that they were buried with the best and most luxurious provisions for their afterlife. Discovering unimaginable riches and lavish artifacts in ancient tombs is to be expected, but sometimes, excavations offer us the unexpected and archaeologists make discoveries totally different from what they imagined they would find. Whether they are gruesome, shocking, or simply strange, discoveries like these are important to enlighten us about the rituals, beliefs, and policies of ancient cultures.

10) The Death Pits within the Royal Tombs of Ur

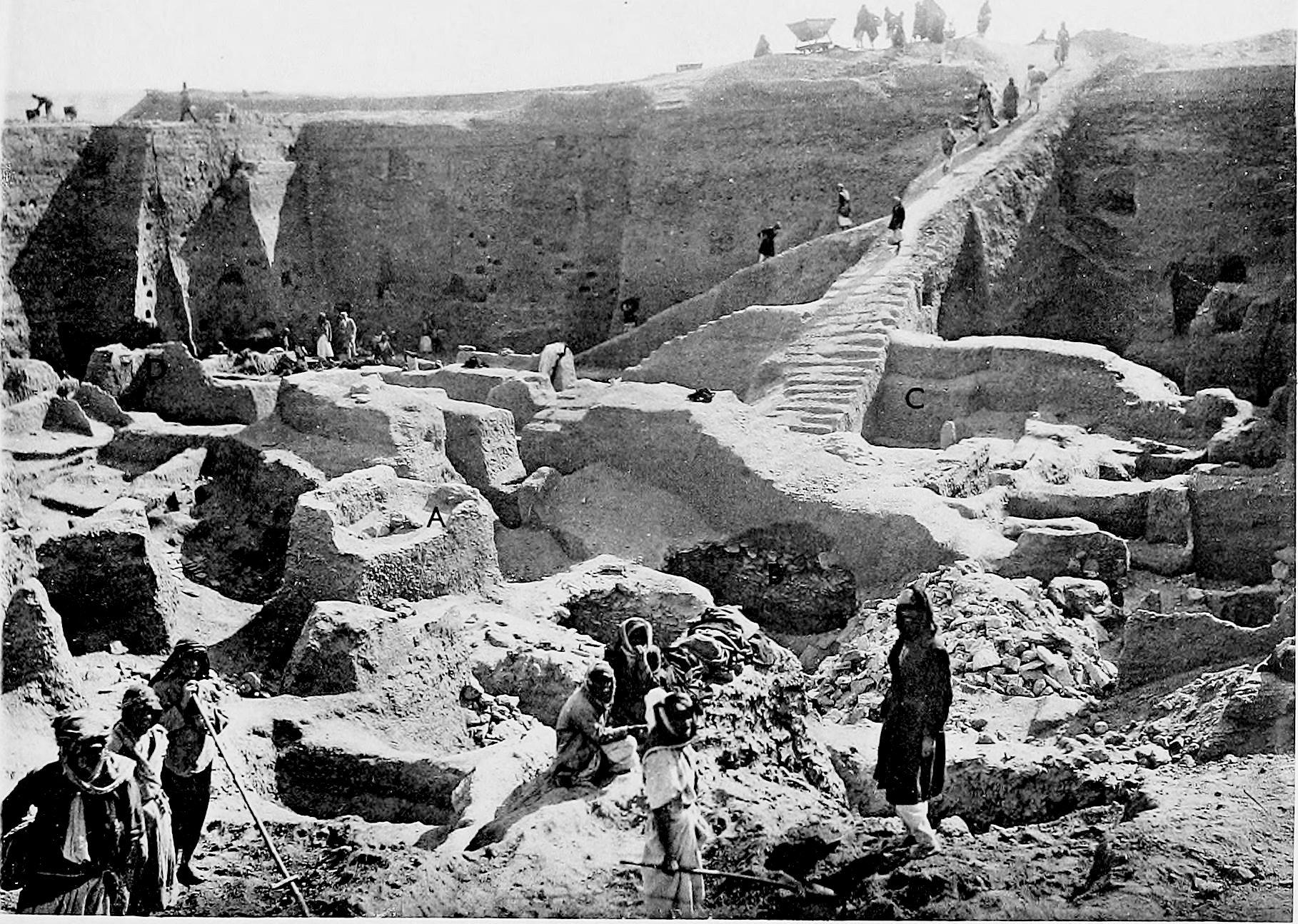

The Royal Cemetery of Ur, an archaeological site in modern-day Iraq, has first been excavated between the years of 1922 and 1934. Of the circa 2000 burials that were uncovered at the site, 16 have been identified as royals. These graves contain ancient Mesopotamian kings and queens from the so-called Early Dynastic Period IIIA, which spans the years between 2600 and 2450 BC. The ancient city was abandoned due to the Euphrates river changing its course over two millennia ago, and in an age before modern-day plumbing, close proximity to a body of water was a necessity for a flourishing city.

Discovering hundreds of tombs filled with fascinating artifacts was exciting enough, but that was not all. The evidence of human sacrifice on a gigantic scale shocked both professional archaeologists and the hired local helpers.

Below the graves of the royals, several death pits have been uncovered, which contain between 7 and up to the unbelievable number of 74 bodies. At first, archaeologists believed that the attendants to the rulers sacrificed themselves by drinking poison, a comparably painless death.

In later examinations and with the help of reconstructions of several skulls, researchers realized that these people had actually been murdered with a sharp instrument. This was only the first step in the extensive ritual. After being killed, the bodies were heated and treated with mercury, which delayed composition. Afterward, they were dressed and placed in ceremonial rows.

The meaning of this elaborate ritual cannot be fully reconstructed. It is clear, though, that this very public display of monarchial cruelty emphasized the duality between the rich and the poor.

9) Liquid Mercury Beneath a Temple in Mexico

As the largest city in ancient America, Teotihuacan, located in modern-day New Mexico, had a population of over 200,000 residents. Even though hundreds of excavations took place at the site, it took quite a while until the first evidence of a royal tomb was discovered.

Further excavations to find the royal tomb took place beneath the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, an Aztec deity of learning, knowledge, and priesthood. The discovery made in 2015 brought the excavations to a surprising halt: at the bottom of the tunnel, there was a chamber filled with liquid mercury.

Not only was it very difficult to mine mercury at the time the burial site had been erected, but it was also an incredibly rare element. This signifies that what – or rather: who – lies behind the chamber was to be protected at all costs.

The archaeologists working in the tunnels under the temple now have to wear gear that protects them from mercury poisoning, but the excitement of being on the trail of potentially the first royal tomb to be found in Teotihuacan makes this danger more than worth it for dedicated archaeologists.

8) A Missing Mummy

Sometimes, an unexpected discovery is not what is found but precisely what is not found. When the tomb of Rames | was discovered in 1817.

the team surrounding Italian archaeologist Giovanni Belzoni discovered another large chamber beneath it. This chamber turned out to be another tomb, and a very luxurious one at that: both the ceilings and the walls were intricately painted. The extravagant alabaster sarcophagus in the chamber though was – empty.

It was not before 1828 that the hieroglyphics on the sarcophagus were finally deciphered and the tomb could be identified as that of Seti |, the father of Ramses Il. Seti’s mummy, though, was not found until 81 years later – it had been hidden in another tomb, presumably to keep it safe from grave robbers.

7) Twelve Mummies Sharing One Tomb

As seen with the story of Seti |, the practice of hiding mummies from grave robbers was not uncommon. A more than usual amount of such hidden mummies was discovered in the tomb of Amenhotep Il in the Valley of the Kings. Twelve more royal mummies had been hidden in sections of this king’s tomb, including a female mummy that was at first considered to be Nefertiti, but then turned out to be the daughter of Amenhotep and Queen Tiye.

The establishing of DNA testing has been very helpful in solving problems like this and has contributed greatly to our understanding of the family relations in extinct dynasties.

6) The Oldest String Instrument in Human History

5) A Strange Ape in Lady Xia’’s Tomb

Almost everyone knows the terracotta army guarding the grave of the first emperor of China, Quin Shihuang. His grandmother, Lady Xia, was buried in a tomb that contained artifacts almost equally as mysterious and exciting. Aside from a wealth of expensive objects like jewelry and ceramics, her tomb also contained a significant amount of animals.

Aside from the twelve horses that would have drawn the two carriages that were buried with Lady Xia, she was also interred with several undomesticated animals. Among these are a leopard, an Asian black bear, and several cranes. Most extraordinary proved the skeleton of a gibbon, one of the so-called lesser apes. The skull of this primate was shaped in such an unusual way that researchers reasoned that it must belong to a species that is now extinct. Finds like these are significant for finding out how even very early exploitation of wild animals could have led to the first man-made extinctions.

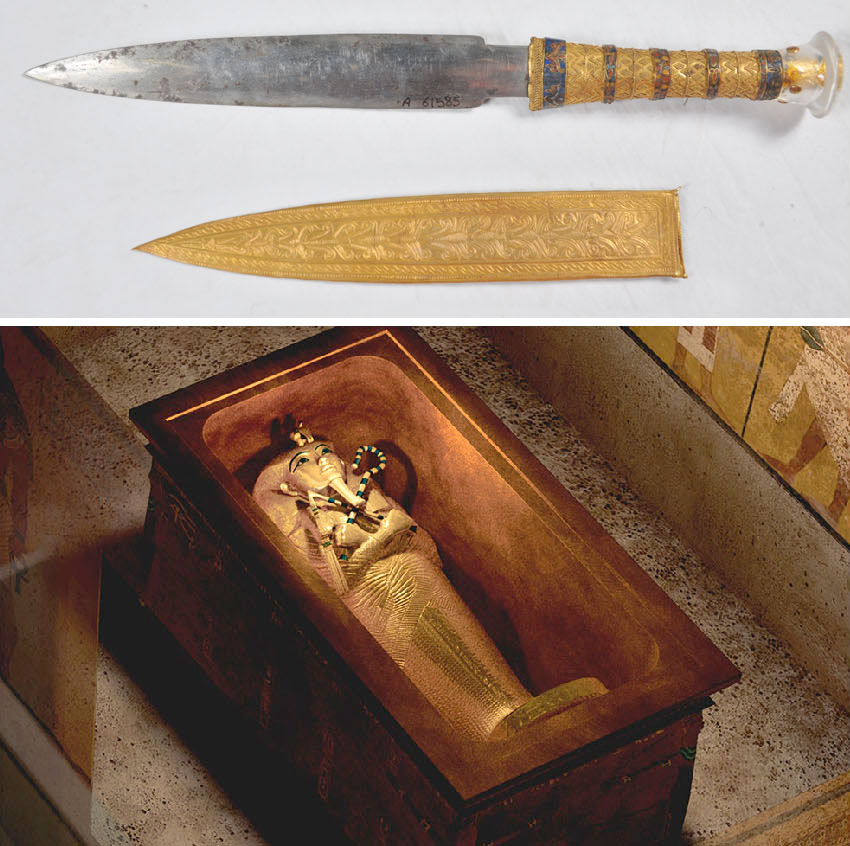

4) The Mysterious Meteorite Dagger

Tutankhamun, commonly known as the boy king, was only nine years when he took the throne and died roughly ten years later. Within the wrappings of the mummified king, there was found a silver dagger with a golden handle and sheath. The blade of this dagger is what is truly special about it: after it had confused scholars since the 1970s, in 2016 researchers were finally able to, with the help of X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, find out its exact composition of iron, nickel, and cobalt. The ratio of these specific composites is similar to that of a meteorite found in Marsa Matruh, a city west of Alexandria. At the time of Tutankhamun’s burial, iron was considered to be more precious than gold, and it was mainly used for gift giving, ceremonial purposes, and

rituals.

3) Jade Burial Suits for a Prince and a Princess

References to burial suits made of jade can be traced back to the Byzantine period and some evidence making their existence plausible has

been discovered in even earlier graves. The first actual complete Jade armor has not been discovered, though. until 1968 when the tomb of Princess Dou Wan and Prince Liu Sheng of the Han dynasty was uncovered. The tomb was very well preserved since it had been protected behind a wall of iron. two brick walls, and a corridor filled with stones.

Crafting these valuable suits must have been hard and diligent work. Each suite is made out of 2000 plates of jade sewn together with gold for the Prince and with silver for the Princess. It is estimated that it would have taken even an extremely skilled jade smith ten years to make one of these suits. For a royal burial, this labor was seen worth it, though: jade was believed to keep away bad spirits and to slow down the process of decay.

2) Tutankhamun’s Unborn Daughters

His young age notwithstanding, Tutankhamun was married to Ankhesenamun, his half-sister and daughter of the pharaoh Akhenaten and Nefertiti. The young couple did not produce an heir, instead, they lost two daughters. One was stillborn after five or six months and the other died shortly after birth.

Amidst the more expensive artifacts in his burial chamber, the box that contains his daughters is relatively plain. A plain, wooden box with a length of only 24 inches contains two small coffins. Tough undecorated and plain. itis apparent that the coffins have been treated very carefully. Both coffins were inscribed with “Osiris”. the name of the Egyptian god of fertility.

The fetuses found in the coffins were found to have skeletal abnormalities like Sprengel’s deformity, as well as scoliosis and spina bifida. This can form a part of the explanation while the girls did not survive. Since marriage inside the family has been pretty common in royals of most cultures, genetic abnormalities are at a higher risk of being carried on, which might have been what has happened in this case.

1) A Ship Under a Pyramid

Pyramids do not only look gigantic and impressive, sometimes they hide something equally gigantic and impressive below. This has been shown, for example, during the excavations that Egyptian archaeologist Kamal el Mallakh undertook in 1954 at the Great Pyramid. When digging under a stone wall at the south side of the pyramid, he at first came across a strange mixture of wood chips, powdered limestone, and charcoal. What he found in the end what a ship with a length of 144 feet – carefully removing each of the ship’s 1224 pieces took two years. The vessel is now mostly known as the Khufu boat, named after King Cheops for whom it likely was built. It likely had the function of a “solar barge” – a ship that would carry the resurrected king with the sun god Ra into his afterlife. It is apparent that this ship was not only built for ritual and symbolic purposes since it bears since of having traveled in water. Some suggest that it has been used as a funerary barge and carried the embalmed king from Memphis to Giza, but others propose that Cheops might also have used it while he was still alive. for example, when undertaking pilgrimages to holy places. Since the 1980s, the reconstructed boat can be explored in the Giza Solar boat museum.